Who was F.M. Alexander?

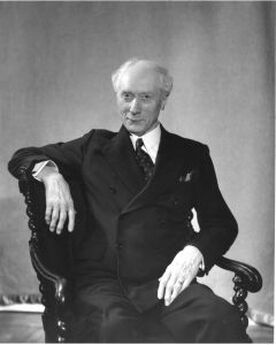

F.M. Alexander - founder of The Alexander Technique

F.M. Alexander - founder of The Alexander Technique

Frederick Matthias Alexander was born in Tasmania in 1869 and as a bright schoolboy developed a love of Shakespeare. On leaving school he pursued a career as a reciter and after initial success, Alexander started to experience problems with his voice that threatened to end his career. Consultations with doctors revealed that no obvious condition caused the problem and advised him to rest before an engagement.

Even with complete rest for up to two weeks the problem would surface half way through a performance. Alexander observed this mainly occurred on stage and rarely with normal conversation. From this he concluded he must have been doing something different during a performance compared to what he did off stage.

Using mirrors, he noticed that when about to recite he would pull his head back and down, depress the larynx and start to suck in air. His body appeared to fix the position with the effect of shortening his whole stature. This fixed position restricted movement thereby having an impact on his breathing, resulting in the audible sucking in of air.

The advice from his tutor to ‘take hold of the stage with the feet’ had been done literally until it became a subconscious habit. Every time he stood in front of an audience the stimulus to recite would activate the response to pull back his head and adopt this unnatural rigid position.

Even with complete rest for up to two weeks the problem would surface half way through a performance. Alexander observed this mainly occurred on stage and rarely with normal conversation. From this he concluded he must have been doing something different during a performance compared to what he did off stage.

Using mirrors, he noticed that when about to recite he would pull his head back and down, depress the larynx and start to suck in air. His body appeared to fix the position with the effect of shortening his whole stature. This fixed position restricted movement thereby having an impact on his breathing, resulting in the audible sucking in of air.

The advice from his tutor to ‘take hold of the stage with the feet’ had been done literally until it became a subconscious habit. Every time he stood in front of an audience the stimulus to recite would activate the response to pull back his head and adopt this unnatural rigid position.

It Ain't What You Do... It's The Way That You Do It!

F.M's early days as a reciter

F.M's early days as a reciter

Now that Alexander was aware of the problem, he assumed that to put it right would just be a matter of not pulling his head back during a performance. However, when attempting to apply the solution of putting his head forward and up he observed that he was still pulling his head back and down.

He had made an unreasonable assumption that we all make when attempting to address a problem. We believe that once we have found the cause it is a simple matter for us to do something in order to improve.

What we do not ask ourselves is, if we knew what it was we had to do, then why were we not doing it in the first place? In Alexander’s case, his problem was because he was doing something he should not have been doing, that is, stiffening the neck. To correct this he had to first stop stiffening his neck before he tried anything else.

When he attempted to put his head forward and up, he did it using the habitual tension in his neck he created in readiness to recite. He was never going to find a ‘cure’ if all attempts to improve included this tension. His radical solution was to learn how to stop the unnecessary habitual actions to allow a return to poise. When he succeeded in doing this he observed a marked improvement in his general stature and an end to his difficulties. In addition to these benefits, other health problems that had troubled him from an early age also improved.

He had made an unreasonable assumption that we all make when attempting to address a problem. We believe that once we have found the cause it is a simple matter for us to do something in order to improve.

What we do not ask ourselves is, if we knew what it was we had to do, then why were we not doing it in the first place? In Alexander’s case, his problem was because he was doing something he should not have been doing, that is, stiffening the neck. To correct this he had to first stop stiffening his neck before he tried anything else.

When he attempted to put his head forward and up, he did it using the habitual tension in his neck he created in readiness to recite. He was never going to find a ‘cure’ if all attempts to improve included this tension. His radical solution was to learn how to stop the unnecessary habitual actions to allow a return to poise. When he succeeded in doing this he observed a marked improvement in his general stature and an end to his difficulties. In addition to these benefits, other health problems that had troubled him from an early age also improved.

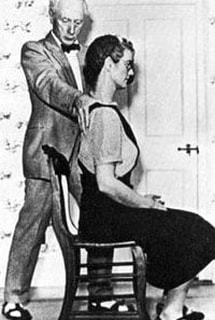

Hands-on teaching

Hands-on teaching

The change in Alexander’s performance did not go unnoticed and he began to receive requests from other actors to learn his technique. He soon discovered verbal instruction alone was not sufficient as it could easily be misinterpreted. The next important step in the development of the technique was learning how to convey the kinaesthetic (feeling) experience necessary to promote change. Alexander found the only way to achieve this was by using his hands to gently guide the pupil through movement whilst preventing the habitual muscular effort.

He was surprised to find the same poor habits that had troubled him existed in all his pupils. As word spread of his technique, doctors began to send patients not responding to conventional treatment for lessons. They observed many ailments improved or completely disappeared following tuition. Encouraged by his success he came to London in 1903 and set about teaching some of the top actors of the day. His theory was generally well received but many dismissed these ‘ramblings of an Australian actor’.

In 1937 eighteen doctors signed a letter published in the British Medical Journal stating that a diagnosis of an illness In 1937 eighteen doctors signed a letter published in the British Medical Journal stating that a diagnosis of an illness was incomplete unless the habitual manner the patients ‘used’ themselves was taken into account. They urged the Council to incorporate Alexander’s work in the medical curriculum.

He was surprised to find the same poor habits that had troubled him existed in all his pupils. As word spread of his technique, doctors began to send patients not responding to conventional treatment for lessons. They observed many ailments improved or completely disappeared following tuition. Encouraged by his success he came to London in 1903 and set about teaching some of the top actors of the day. His theory was generally well received but many dismissed these ‘ramblings of an Australian actor’.

In 1937 eighteen doctors signed a letter published in the British Medical Journal stating that a diagnosis of an illness In 1937 eighteen doctors signed a letter published in the British Medical Journal stating that a diagnosis of an illness was incomplete unless the habitual manner the patients ‘used’ themselves was taken into account. They urged the Council to incorporate Alexander’s work in the medical curriculum.

Going Global

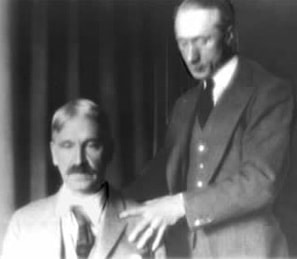

F.M. with John Dewey

F.M. with John Dewey

During the two world wars, Alexander travelled to the United States and gained support from the eminent educationalist, Professor John Dewey. Unfortunately, as in England, the critics who argued against the technique were both influential and unwilling to have lessons from ‘a very unconventional physician’ or ‘an Australian of original but uncultivated mind’.

Dewey commented on these academic thinkers as people who adopted their position early in their careers, and then used their intellects to defend it indefinitely. This he concluded proved Alexander’s point that habits were indeed hard to change.

In 1948 Alexander successfully sued Dr Ernst Jokl, a South African doctor and authority on physical exercise, who had referred to the technique as ‘quackery’. Dr. Jokl was the physical education officer for the South African Government and had written an article attacking Alexander in response to the idea of introducing the technique into the school system.

The head of the Transvaal Teachers Association Mr I. Griffith had earlier praised Alexander’s work dismissing the existing physical culture, deep breathing and relaxation exercises as virtually worthless. In his address to the annual conference he said: -

"Even a very small acquaintance with Alexander’s work causes serious doubts concerning the wisdom of teaching physical training to our children. In this subject we make children perform movements and exercises completely unrelated to anything they do in school or at any other time ..… If a bad manner of use exists, and it exists in almost every person, that same bad manner of use will be employed to perform these specific exercises and cannot therefore bring about any improvement.."

At the trial, testimonies given by scientists and physicians, many as pupils of the technique, established Alexander’s work was based on sound scientific theory. Alexander won the case.

In London the first Alexander teacher training centre was established in 1936 requiring students to complete a three-year course to qualify. Alexander continued to teach until his death in 1955.

Dewey commented on these academic thinkers as people who adopted their position early in their careers, and then used their intellects to defend it indefinitely. This he concluded proved Alexander’s point that habits were indeed hard to change.

In 1948 Alexander successfully sued Dr Ernst Jokl, a South African doctor and authority on physical exercise, who had referred to the technique as ‘quackery’. Dr. Jokl was the physical education officer for the South African Government and had written an article attacking Alexander in response to the idea of introducing the technique into the school system.

The head of the Transvaal Teachers Association Mr I. Griffith had earlier praised Alexander’s work dismissing the existing physical culture, deep breathing and relaxation exercises as virtually worthless. In his address to the annual conference he said: -

"Even a very small acquaintance with Alexander’s work causes serious doubts concerning the wisdom of teaching physical training to our children. In this subject we make children perform movements and exercises completely unrelated to anything they do in school or at any other time ..… If a bad manner of use exists, and it exists in almost every person, that same bad manner of use will be employed to perform these specific exercises and cannot therefore bring about any improvement.."

At the trial, testimonies given by scientists and physicians, many as pupils of the technique, established Alexander’s work was based on sound scientific theory. Alexander won the case.

In London the first Alexander teacher training centre was established in 1936 requiring students to complete a three-year course to qualify. Alexander continued to teach until his death in 1955.

|

|

Further reading...

Michael Bloch's biography of FM Alexander is a 'warts 'n all' account of the remarkable life of the founder of the Alexander Technique. I can thoroughly recommend it! |